Stenhouse Books

Stenhouse, now a part of Routledge, publishes professional books written: “for teachers, by teachers.” We believe in creating a space for teachers’ voices, and we believe in the power of professional books to be such a space for educators to learn from one another’s ideas, practices, and expertise.

Featured Book Collections

Featured Books

Shifting the Balance, Grades K-2 (1st ed.)

6 Ways to Bring the Science of Reading into the Balanced Literacy Classroom

This best-selling guide is concise and practical, integrating effective reading strategies from each perspective. Every chapter of Shifting the Balance, Grades K-2 focuses on one of the six simple and scientifically sound shifts reading teachers can make to strengthen their approach to early reading instruction

Shifting the Balance, Grades 3-5 (1st ed.)

6 Ways to Bring the Science of Reading into the Upper Elementary Classroom

The authors offer a refreshing approach that is respectful, accessible, and practical – grounded in an earnest commitment to building a bridge between research and classroom practice. As with the first Shifting the Balance, they aim to keep students at the forefront of reading instruction.

Podcast - Shifting the Balance, Grades 3-5

The much anticipated follow-up to Shifting the Balance is now available. In their hugely popular The Six Shifts Podcast, the authors Jan Burkins and Kari Yates, together with co-author Katie Cunningham, extend the conversation to Grades 3-5 and through seven brand new episodes introduce six new shifts to bring the science of reading into the upper elementary classroom.

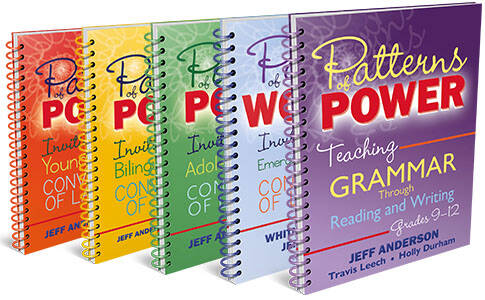

Patterns of Power Series

A flexible collection of resources that supports an authentic, inquiry-based approach to grammar instruction by inviting students to uncover and appreciate writing's beauty and meaning.

Learn More about the Patterns of Power Book SeriesMeet the Authors of Shifting the Balance

Dr. Jan Burkins

Dr. Jan Burkins was an elementary classroom teacher for seven years and a literacy coach for seven years. She has worked as a part-time assistant professor, a district literacy leader, and is currently a fulltime writer and consultant. Jan’s current work includes speaking engagements, presentations at conferences, and professional learning support for school districts.

Kari Yates

Kari Yates is an author, speaker, consultant and staff developer with a passion for helping busy literacy educators thrive. Kari has a passion for helping teachers, coaches, and administrators find the inspiration, courage, and resources to nurture joyful, and authentic literacy learning, one next-step at a time.

Katie Egan Cunningham

Katie Egan Cunningham has twenty years of experience as an educator in many different roles to support students and teachers including classroom teacher, literacy specialist, literacy consultant, and teacher educator. Katie is an Associate Professor of Literacy and English Education at Manhattanville College and her research and teaching focus on student and teacher happiness, literacy methods, new technologies, critical literacies, and children’s literature.